With the capitulation of Fort Niagara in July of 1759, civilians not accompanying the French forces into captivity were transferred by flag of truce from Oswego to an island in the St. Lawrence River. Accompanying these 26 women and children were a servant and the garrisons’ priest, a Franciscan friar from the reformed Recollect branch of the order. While the Recollects had friaries like their brown-habited Conventual brethren as retreat centers for prayer, penance, and spiritual reflection, they were an outgrowth of the grey-clad Observant friars who simultaneously emphasized returning to a stricter interpretation of the poverty espoused by St. Francis. For some friars in 16thC Spain even the Observant order did not follow the vow of poverty strictly enough, leading them to take more ascetical practices and go barefoot in emulation of the earliest Franciscans. By 1585 communities observing this interpretation began to be established in France, with one being established in Paris itself by 1603. With a zeal for missionary work as well as poverty and reflection (a balance Francis sought and alluded to in his rule for hermitages), the Recollects would become Canada’s first missionaries by 1615, serving until the English capture of Quebec in 1629. Followed by the Jesuits, the Recollects would not return to Canada again until 1670 when they would serve the crown as official chaplains for military garrisons and aboard naval vessels in addition to acting as missionaries. Disallowed from receiving novices after the British conquest in 1759, the orders’ presence in Canada would dwindle until 1813 with the death of the last remaining priest, Louis Demers. Given an increasing interest in recreating the Recollect friars for historical interpretation in Canada and the US, these introductory notes have been assembled to assist costumers and living historians in developing a historically correct base kit for their interpretive programs.

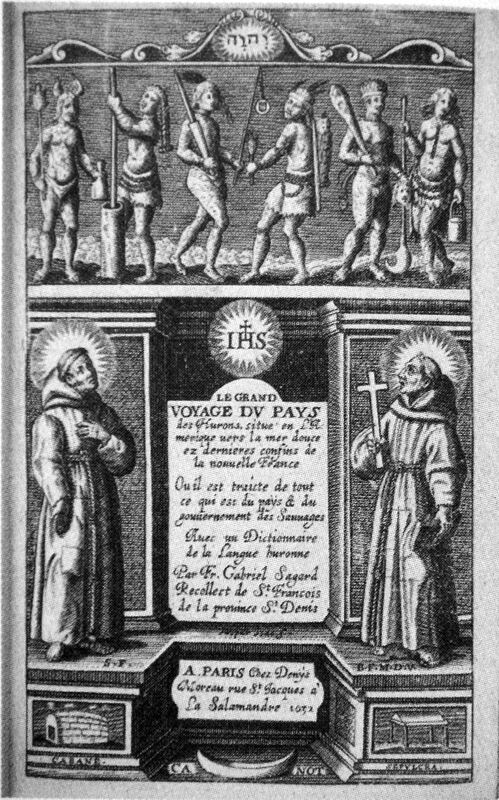

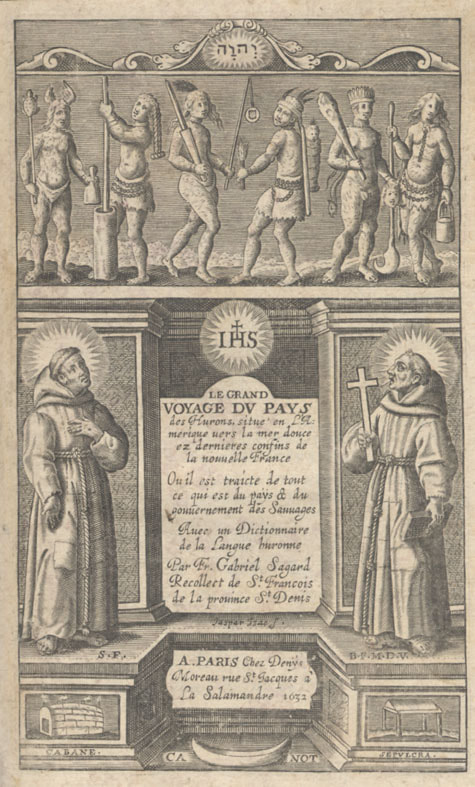

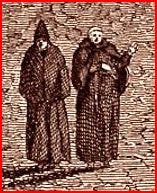

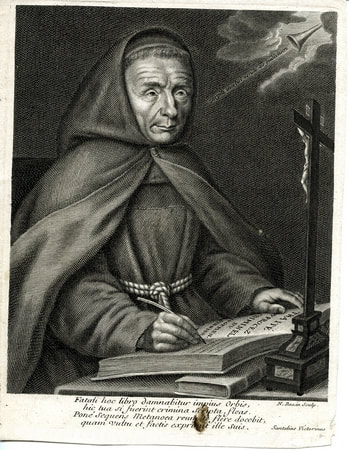

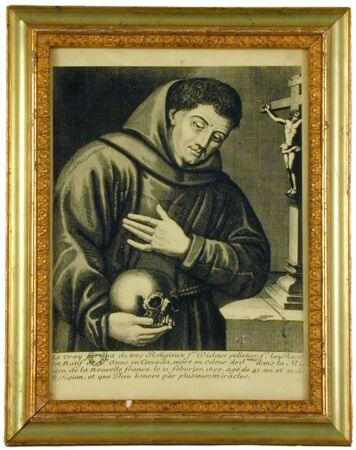

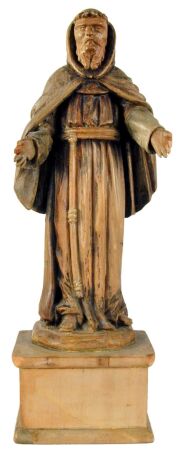

To begin, it is important to understand what the end product should look like. Fortunately a number of original drawings, paintings, and statues depicting Recollect Franciscans have survived.

To begin, it is important to understand what the end product should look like. Fortunately a number of original drawings, paintings, and statues depicting Recollect Franciscans have survived.

To achieve the depicted look, the habit needs to incorporate the following:

- Twilled wool. Just like their Spanish counterparts, the Recollet friars were using cheap coarsely woven twilled wool that utilized yarn in different colors for the warp and weft (sheep's black/grey and white). Having the right material is critical as it not only has the right look and texture but also drapes and folds appropriately when worn. At this time, the only suitable material commercially available is Woolsome's "Wool Medium Twill Diagonal White Black – WMT 0209/01" available at:

- https://www.woolsome.shop/product/wool-medium-twill-diagonal-white-black-wmt-0209-01/

- NOTE: while the material and shipping from Europe is not inexpensive, you only need to make 1 habit, simply patching it over time and the more worn/patched it becomes the look improves (having said that do NOT artificially age the habit, simply wear it).

- Pointed hoods with cowls. Interestingly, the recollects during this period used pointed hoods while most observants in France were still using rounded ones. Make sure to adjust the habit pattern accordingly. Patterns are included below, but details on how to transcribe the patterns and construct the habits will be coming in future posts. Cowls should drape about 2 finger widths below the shoulder point, any larger and they start looking like a horribly incorrect costume shop habit.

- Shaped sleeves. As can be seen, sleeves are fuller above the elbow and narrow from there to the wrist. This is due to an unique sleeve shape that will be discussed in upcoming posts on patterning and construction. Basically, instead of simple rectangular sleeves, one end is shortened for the wrist and elongated-S curve is utilized along the bottom seam.

- Hooded cloaks. In addition to having the separate hood/cowl worn over the robe, cloaks with their own pointed hoods and closing by 1-2 buttons at the neck were utilized while travelling and in colder weather. Hoods on both cloaks and habits were made of two layers of fabric, so effectively this provides 4 layers of warmth with air/insulation space between them when worn in winter. Cloaks were also most commonly made from grey twilled wool.

- Cincture. Recollects appear to have used the typical cincture consisting of ~1/2" diameter hemp rope (natural hemp color, not white). A future post will be made on how to tie them, but essentially it is a loop with a sliding taut line hitch and then the free end has the knots for the three vows worked into it. This provides an adjustable size loop (and is why they look like two ropes going around the waist instead of one) and leaves a single end to hang down.

- NO CRUCIFIXES AROUND NECK. Wearing crosses around the neck does show up in the 1740s and later among Capuchin Franciscan missionaries in Africa, but the practice is very uncommon and I have yet to see any evidence to date for doing so among Recollect friars, particularly in New France, during this era. If a rosary is worn in order to make the impression clear to site visitors, it is best to loop it around the cincture and let it hang at the waist instead.

- Bare(d)foot. Simply put, Recollect Franciscans did not wear shoes and went either barefoot or in wooden clogs (NOT the Dutch style), even in the snow and ice. Having tested this in Michigan for a weekend it is doable but unpleasant and interpreters MUST be constantly vigilant for frostbite and maintaining a fire they can retreat to frequently for warming up. While I have not found any accounts of friars utilizing them, wool scraps utilized as footwraps may be a suitable accommodation while traversing through snow during winter (then going barefoot once inside by a fireplace).

- MISCELLANEOUS. It is currently unknown what recollects wore under their habits outside of a priest buried in Detroit in 1701 who only had a hair shirt (cilice) for penance underneath. Open-kneed linen drawers. a second wool or linen robe (tunic), and indigenous loincloths all may have been used as underwear but frequently it was up to the individual friars whether to wear their allotted linens or give them away. The only evidence we have to date for headwear is the aforementioned burial where the priest was also wearing a red knit cap (toque) similar to the one found on the Machault shipwreck and worn throughout New France. Other posts will have to be forthcoming for details on the various books, church implements, rosaries, trade goods, and personal gear a recollect interpreter should have on display. These items would be transported in a wallet, a flat rectangular linen sack with a slit in the middle of one side which is filled in each end, twisted in the middle, and tossed over a shoulder.

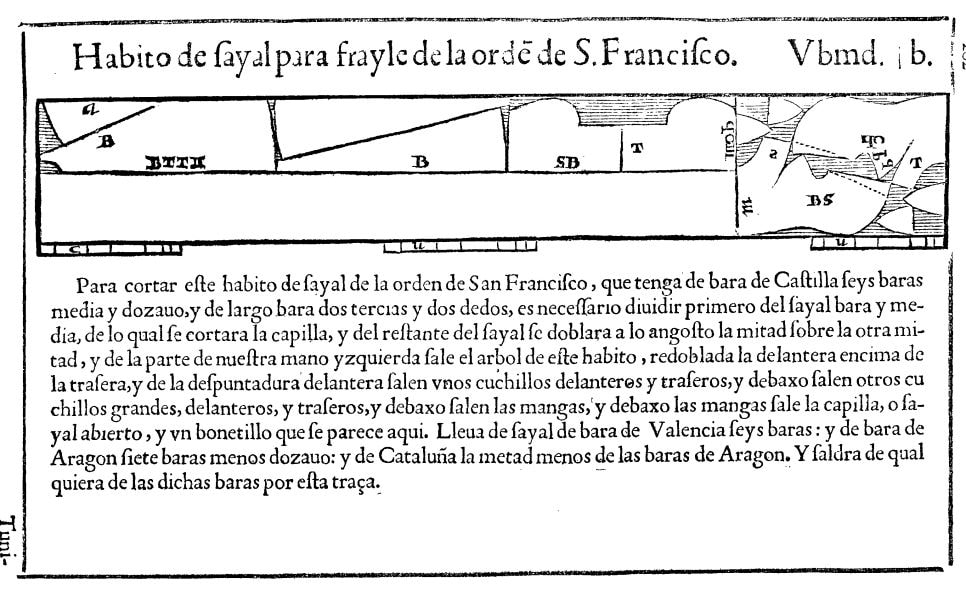

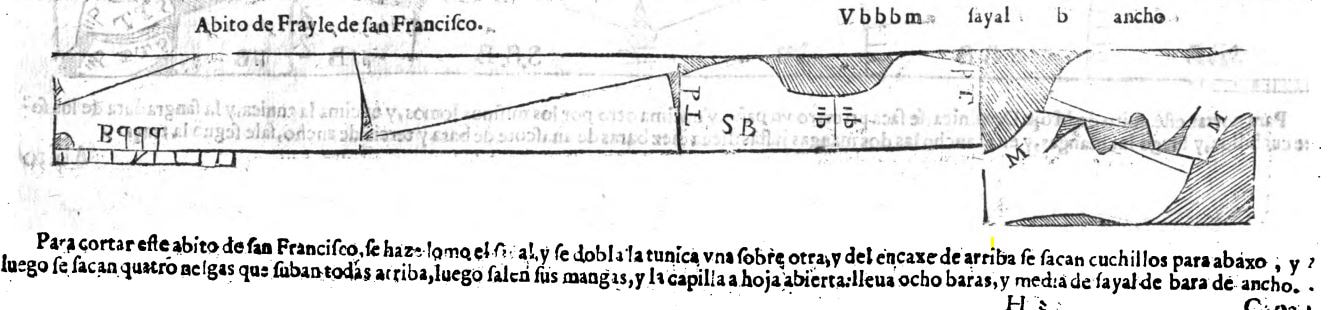

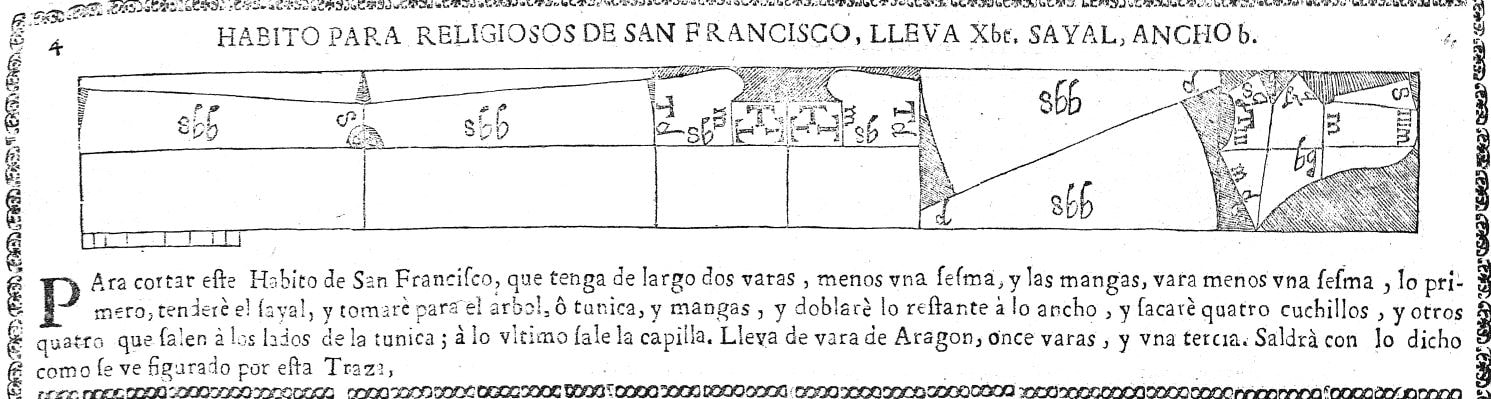

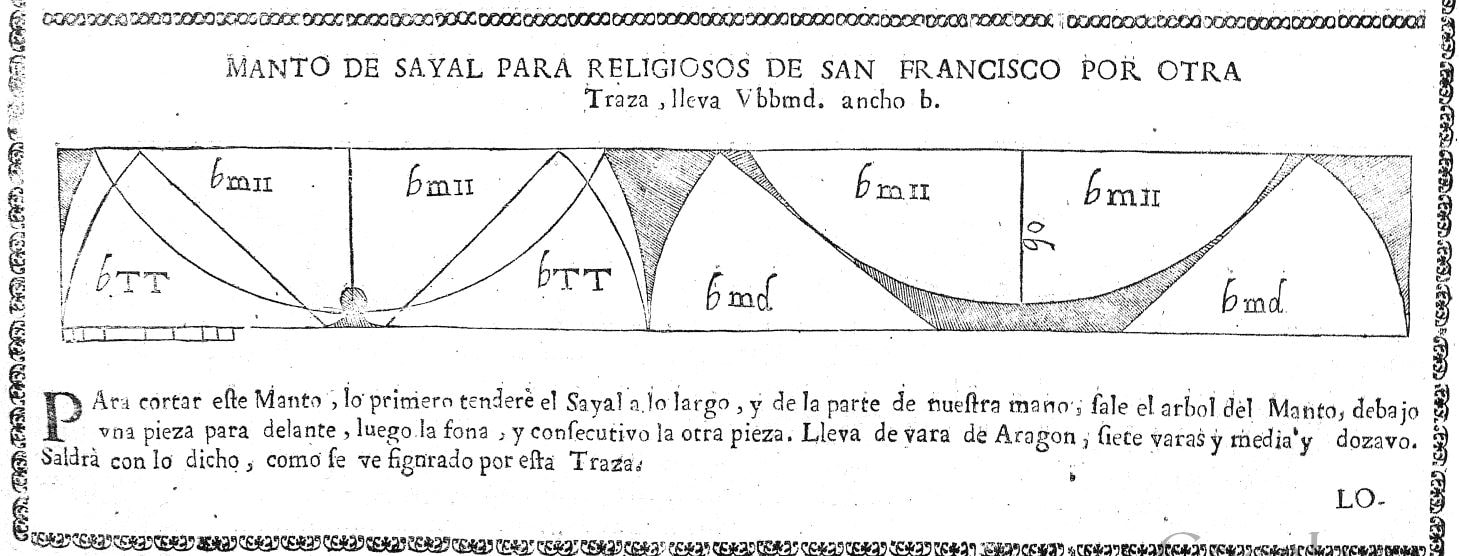

As you can see, the devil is quite literally in the details and in addition to using the right material it is also important to integrate the proper elements when it comes to cut and construction. Unfortunately, a surviving original pattern for a recollect Franciscan habit has not been able to be located at this time, but Spanish patterns exist that when constructed are very close to the habits in the recollect depictions. Future posts are planned to elucidate how to go about laying out and constructing the patterns, but for now they are included below as a starting point for advanced costumers.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed